Today I made my way into the old part of Guiyang to hear a personal concert of Guqin music by one Guqin Master Wu. The Guqin (where the ‘q’ is pronounced more like ‘tsch’ than ‘kwe’) is a 7-stringed Chinese instrument, a bit like a zither, and its strings are traditionally made of silk. Much of Guqin music was created by scholars thousands of years ago and the instrument is linked to other ancient elements of Chinese culture such as calligraphy, Zen Buddhism and the tea ceremony. When we entered the idyllic courtyard, surrounded by ornate and quiet buildings and filled with trees and singing birds, I immediately felt a sense of calm- and sure enough, the Guqin, with its tranquil unobtrusive timbre and volume, was played in order to support and provide a background for contemplation and scholarly pursuits. The sense of tranquility seemed to chime with what I’d thought were Japanese values- and tea ceremonies I’d also tended to associate with Japan. But Kerun told me these traditions in fact originated in China.

Then, under the trees, Master Wu performed for us.

The following piece, Flowing Water, part of a longer whole, High Mountain, Flowing Water, is based on the legendary friendship between Guqin master, Yu Boya, and Zhong Ziqi, his rustic woodsman friend. Master Wu explained that all Guqin pieces have titles which set a scene or evoke an atmosphere in some way. And different playing techniques are designed to symbolise different things- harmonics or overtones, the sky; full string plucks, the earth; and glissandi or ‘bent’ notes, the human voice.

The Guqin is sometimes played with other quieter instruments. It is also used to accompany songs or settings of literature, as in the following example:

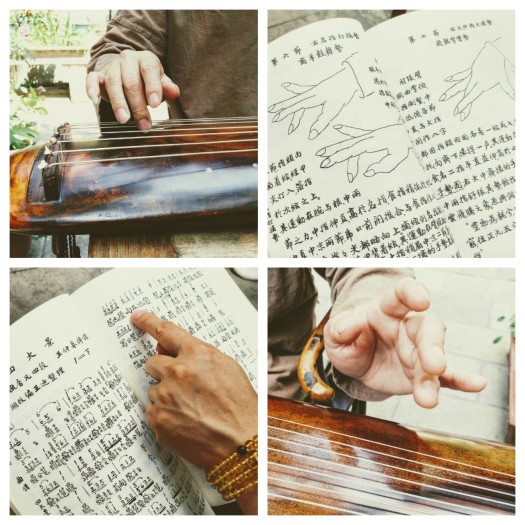

After he’d played, Master Wu showed us a book of Guqin hand positions and gestures, and Guqin notation which is made up of Guqin-specific Chinese characters. Some parts of a character mean to pluck the string backwards, others mean to flick it forwards with the top of the nail, others still mean to play more than one string at once, and so on. There is nothing in the notation to indicate rhythm or phrasing, so there is space for performers to interpret- or in some way improvise through- the ancient scores.

And then happily for me, I got to have a go on the Guqin for myself- guided by one of Master Wu’s students, who also performed for us.

Leaving Master Wu and his students in the peaceful courtyard, Kerun and I headed out in bustling Guiyang old town. It felt good to soak up a bit of the everyday and to orientate myself in the city a little more.

In a shopping district in the west of the city- the Shi Xi Road area- we came upon a great example of Chinese people’s love for technology: an interactive street video game triggered by motion sensors. People young and old were playing it all the way up the street. I particularly enjoyed the older woman having a good ol’ game of virtual ten-pin bowling!

We rounded the day off with an obligatory cup of bubble tea before making our way home under the setting sun.

We rounded the day off with an obligatory cup of bubble tea before making our way home under the setting sun.

Thank you so much for this lovely post! I am going to Guiyang in a month, and I’d love to hear master Wu playing the Qin…could you please tell me how to do it/reach him?

Best regards,

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Rui, thanks for your message- exciting you’re visiting Guiyang! I’ve been checking out the best way of hooking you up with the guqin player and since he doesn’t have a website he has just said to pass on his mobile number and you can get in touch. Here are his details: Mr Wu Ruojie 13985171043. Have fun!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your reply and Mr. Wu’s contact! I’ll let you know if i had fun 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person